The different kinds of notes

This is the second entry of three where I go over what I learned from the user research I’ve been doing for Colophon Cards.

The post where I outline my general theory of notetaking for all to disagree with #

At the end of my last post, I mentioned that I had switched to pen and paper notetaking in the early 2010s, after years of serious digital notetaking using plain text files.

I wrote about how much more enjoyable the analogue notetaking was but what I didn’t mention was why I abandoned my plain text system. Nor did I write about my first foray into serious notetaking.

The notebook above, from 1994, is the oldest notebook of mine I’ve found. It’s the first proper notebook I kept. It wasn’t a journal, sketchbook, drafts, or workbook for school. Just notes.

And it petered out pretty quickly. I had forgotten all about it until I found it in a box a few months ago. For a good reason: it was a random mess that I didn’t take seriously.

Notetaking seriousness didn’t come for me until college, which makes sense. College is when I first started to test myself with more structured projects. Essays, theses, and my early blogging, all required a little bit more thought and planning than a teenager’s haphazard writing hobby.

Serious writing required serious notetaking, both in terms of scheduling and structure. For years, I had a strict notetaking system. Each day I made a new text file with the current date as a file name. Each file was filled with whatever notes I needed for whatever I was working on at the time. Every day I wrote something, I crossed it off on the calendar with a black marker. On the days when I didn’t write something, I marked in red.

The goal was to keep the run of black unbroken. It worked. Sort of. This regimented system was based on a random quote from Jerry Seinfeld, of all people, and a misunderstanding on my part of the purpose of Julia Cameron’s Morning Pages from her book The Artist’s Way.

I’d fallen into one of the oldest process trap of all: I had cargo culted methods whose principles, concepts, and motivations I did not understand. I had copied the ritual without understanding the mechanism.

Over time this turned into a slog, _no matter what, write three pages!, and by the time I got to my PhD, it made everything about a bad experience worse.

When I began my PhD in 2001, we were all still recovering from the dot-com crash. It made sense to work on a thesis that was grounded in an evolutionary, small-c conservative, view of media. Not only was web- and new media scepticism abundant at the time, it was very strong in the specific academic environment where I was working. Over the years that I worked on my PhD, that view became untenable to me. Interactive media—the web—was and is fundamentally different from its predecessors, in a way that promised to be completely revolutionary to both culture and society. But I was locked in a reactionary thesis. Starting from scratch would have almost inevitably led to me having to abandon the PhD. This meant that I had to write a thesis I utterly disagreed with, making an argument I didn’t believe in, using references that I felt were borderline nonsense in the context I was pulling them into, and making the words I wrote feel like ash.

The regimented daily pages notetaking routine made everything worse. It turned the writing process into a multi-year death march, filling the folders of my hard drive with unusable nonsense that I didn’t believe in then and don’t believe in now.

I managed to complete and defend my PhD and swore to leave academia behind for the rest of my life.

It took me years to fully recover.

To get there—to recover from my unrelenting thesis death march—I had to get more thoughtful and serious about writing and my notetaking. As is the way of my people (overthinkers, that is), this meant research. Lots and lots of research. On writing. On creativity. On notes and notetaking. On planning. Even research on skills development, the cognitive component in expertise, as well as memory formation. I dug through the entire Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance (over 900 pages). I read fluffy, self-help books on creativity. I read serious studies on the effects stress has on memory formation. I read old books. I read new books. Some of them dated. Some of them timeless. Some worked. Some didn’t.

I also began to understand the mechanism behind Julia Cameron’s morning pages, how it was supposed to work, and what it had in common with other approaches, even the ones that superficially look completely different.

I began to understand, at least for my own purposes, what notetaking was for.

And I think—based on the research I’ve been doing—that I’m not alone.

It’s all about boxes and maps.

The different kinds of notes #

I recently interviewed about a dozen people on their notetaking habits. Before that, I had done a survey.

There’s a lot to cover as notes seem to come in an endless variety. Even from a group as small as twelve people you already got more than twelve different kinds of notetaking:

- Household management (shopping lists, chores, etc.)

- Task management

- Mnemonic notes (write to help you remember)

- Various kinds of annotations

- Shared work notes (meeting minutes, documentation, etc.)

- Personal work notes

- Idea exploration

- Journalling

- Scrapbooking (digital and analogue)

- Research management

- Outlining

- Information management (bookmarks and the like)

- Project management

- Client management

- Concept database (save your ideas)

This is not an exhaustive list. The closer you look, the more varieties of notetaking you find, even in such a small group of people.

There’s a temptation there to dig in, get into even more detail, and generally act as if you’ve hit a motherlode, a vein that’s rich and deep and rewarding. Just really get into it, interview dozens or hundreds of people, do study after study and spend years cataloguing all the varieties of notetaking

But that would be a mistake.

When you’re in a domain where increasing the resolution and detail only reveals an escalating amount of previously undiscovered complexity, odds are you are tackling what E.F. Schumacher called a ‘divergent problem’. These problems aren’t technical. They can’t be broken down into parts to solve each part step by step. A problem like this becomes more complex and hard to solve under close analysis, not simpler and easier to solve. The more detail you see, the more conflicting data points you encounter and the harder it gets to reconcile the diversity you’re witnessing with a cohesive mental model.

From A Guide for the Perplexed, page 126:

I have said that to solve a problem is to kill it. There is nothing wrong with “killing” a convergent problem, for it relates to what remains after life, consciousness, and self-awareness have already been eliminated. But can—or should—divergent problems be killed? (The words “final solution” still have a terrible ring in the ears of my generation.)

Divergent problems cannot be killed; they cannot be solved in the sense of establishing a “correct formula”; they can, however, be transcended. A pair of opposites—like freedom and order—are opposites at the level of ordinary life, but they cease to be opposites at the higher level, the really human level, where self-awareness plays its proper role.

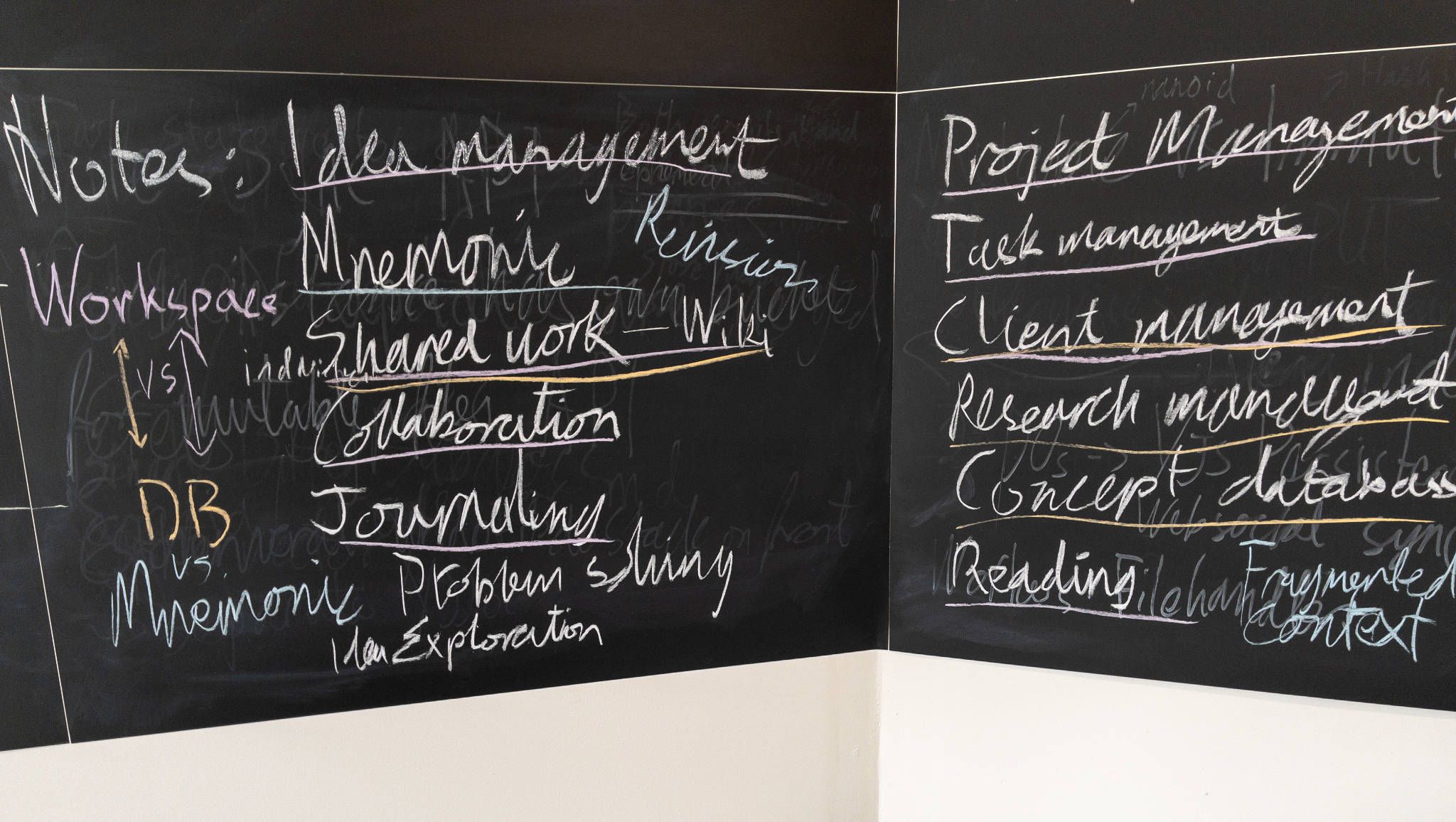

So, when I step back, squint a bit, and stare at my blackboard and my notes, it strikes me that most of the notetaking methods the interviewees described are trying to answer at least one of the three following questions:

- How do I manage my creativity?

- How do I manage my knowledge?

- How do I manage my understanding?

Or, more to the point, the notetaking methods are a way for the writer to continuously ask themselves these questions and adjust their tactics as needed. None of the methods are prescriptive or rigid; they are all constantly being adapted.

The job of notes for creativity is to:

- Generate ideas in a structured way through research and sketching.

- Preserve those ideas.

- Explore the ideas until they have gelled into a cohesive plan or solved a problem.

The job of notes for knowledge is to:

- Extend your memory to help you keep track of useful information (client data, meeting notes, references).

- Connect that information to your current tasks or projects so that you can find it when you need it.

The job of notes for understanding is to:

- Break apart, reframe, and contextualise information and ideas so that they become a part of your own thought process.

- Turn learning into something you can outline in your own words.

In terms of software, that means we have these three broad approaches:

- Notes for creativity tend to favour loosely structured workspaces. Scrivener and Ulysses probably come the closest, though, in practice, I have doubts that either of them is loosely structured enough.

- Notes for knowledge favour databases, ‘everything-buckets’ (apps that expect you to store everything in them), and hypertextual ‘link-everything’ note apps.

- Notes for understanding tend to favour tools that have powerful writing or drawing features (which you favour will depend on your skill set and comfort).

I don’t think you can make software that perfectly serves all three of these kinds of notetaking. Knowledge bases become too rigid to serve as workspaces for creativity. The creative spaces are too loosely structured to work well as knowledge bases. You can integrate writing and drawing tools in either, but that serves notetaking for understanding only up to a point. Most knowledge bases preserve too much detail and context, which gets in the way of reframing and contextualization. And too fully featured writing or drawing tools could make the creativity tools too complex to use.

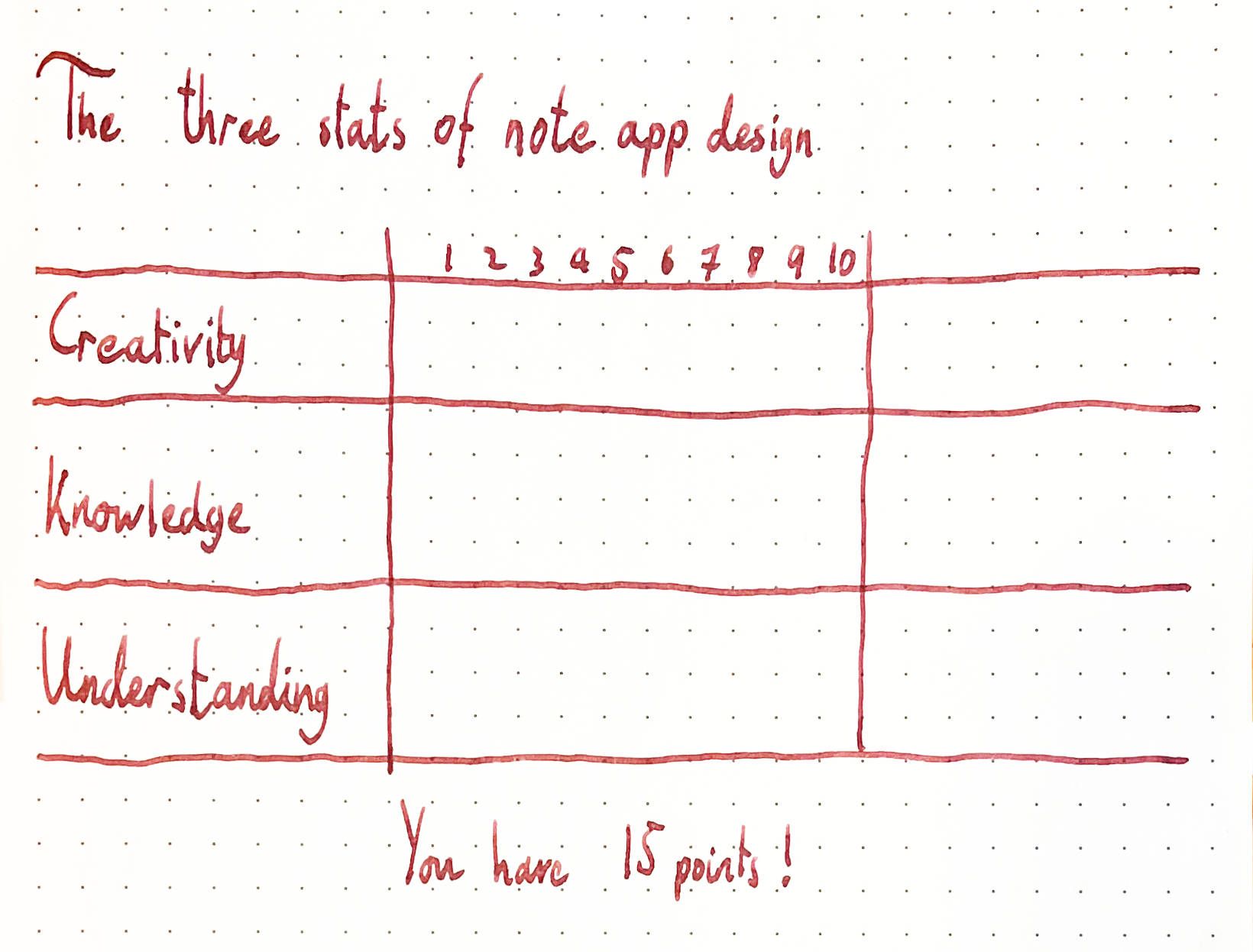

In the parlance of roleplaying games, these are the three character statistics of your notetaking app, and you only get to assign 15 points between them. You could choose to be average in all three (5, 5, 5, uninteresting). You could choose to dump all of the points in one stat and be just plain bad at the rest, which would simplify the design a bit. Or, you could think of it as a priority list: most important, second important, unimportant (dump stat!).

(If you aren’t familiar with RPGs, you can think of them as three sliders with a fixed sum of values between themselves. Every time you push a slider above ‘5’, another slider has to go down a corresponding amount.)

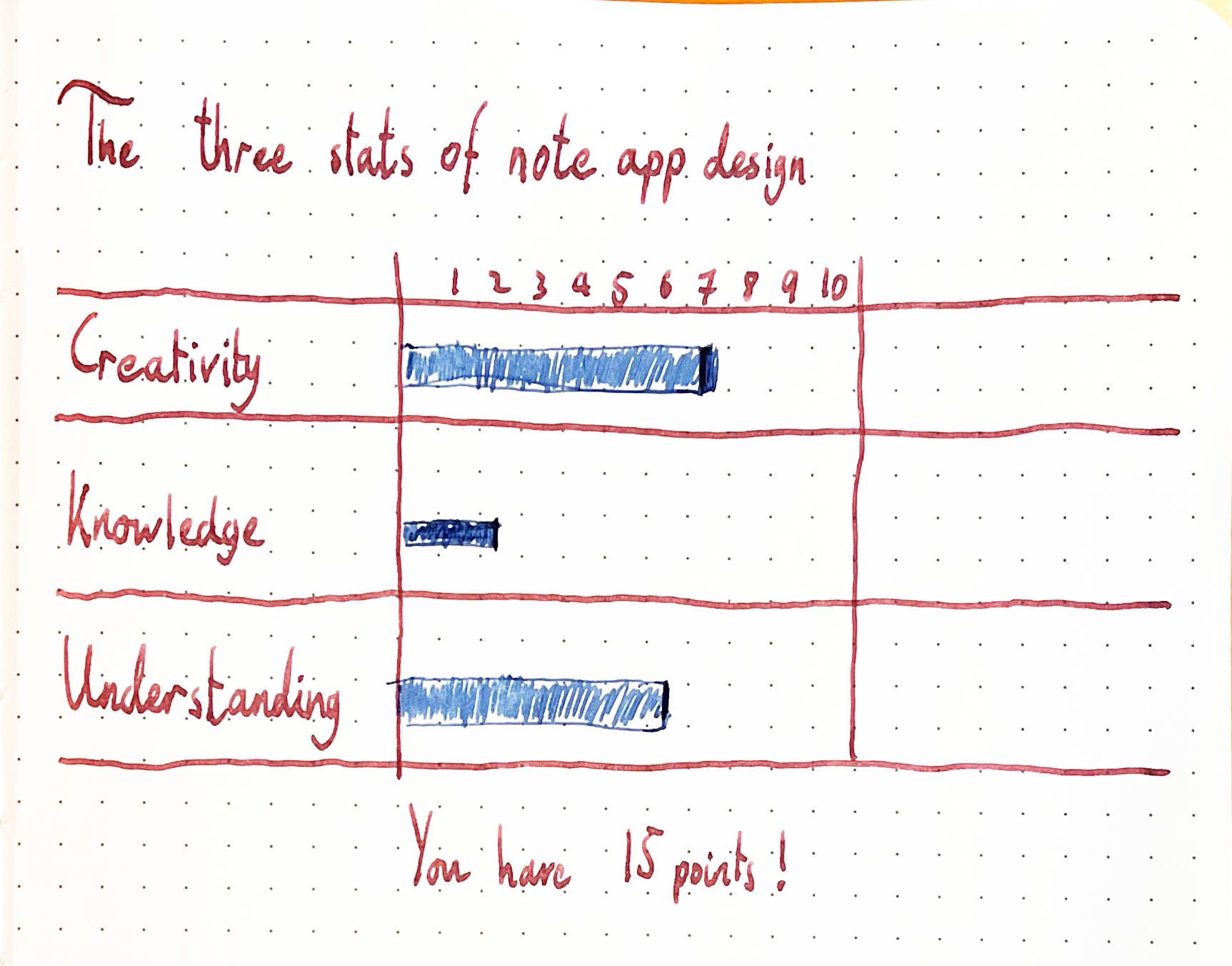

How would I divvy up the points for Colophon Cards? What would the Colophon Cards character sheet look like?

At the moment, I’m leaning towards this:

- Creativity: 7

- Knowledge: 2 (dump stat!)

- Understanding: 6

A workspace that:

- Favours lightweight and flexible structure over detailed organisation and connections.

- Prioritises speed over accuracy when creating and finding notes.

- Has better-than-average writing tools.

Now, I’m not going to pretend that I’m basing those priorities on the comparatively little user research I’ve been doing. They instead represent the kind of app I want to use and enjoy. Because it turns out that enjoyment is essential for long-term notetaking. The research helped me clarify what I wanted, give it focus, and place it properly in the larger context. But, ultimately, I want to make an app I enjoy.

Also, it made me drop a bunch of smaller ideas that research revealed to be less likely to work, but that’s honestly a little less interesting. Though possibly a topic for a future blog post.

Boxes and Maps #

You don’t have to copy the methods of a German academic with a tendency for the abstruse to take notes #

In my relentless daily writing during my PhD, I had missed the point of it. By using a regimented notetaking structure I drove my creativity into the ground, my joy and motivation cratered with it, and burnout inevitably followed.

What I had missed was that the point of these techniques wasn’t to continuously force march forward according to a predetermined master plan. Just writing or getting things done isn’t the purpose, at least not in any of the writing methods I’ve looked at.

And I’ve looked at a few—they all cover some form of notetaking or journaling as a core part of their process:

Umberto Eco’s How to Write a Thesis is a book about writing that contains a fully-formed (and very usable) notetaking system based on index cards. It’s structured so that everything hangs off the Table of Contents or outline. The thesis’s ToC becomes the map you use to structure your notes.

(I wish that I had read Eco’s book before I did my thesis. Alas.)

Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird describes an ad hoc and improvised system of index cards. She presents it as an almost random process but then proceeds to spend an entire chapter explaining the value of a loosely structured notetaking system. Her notes are more of a box full of unsorted items that prod the work forward and guide it.

A good chunk of David Hewson’s Writing: A User Manual is about how various kinds of notes help you write your book. His method has elements of both the Box and the Map. He recommends plotting and planning in advance, but he also uses an unstructured daily journal and a ‘box’ of notes on characters, concepts, places, and ideas to guide the process.

The Story Grid by Shawn Coyne is pretty much just an excel-based, fiction-oriented version of Eco’s “How to Write a Thesis”. Instead of Eco’s table of contents, the story grid uses a list of scenes. But it’s otherwise a very similar principle: the map guides the project and structures your notes. The map evolves as you go but no matter how much it changes it remains the primary organizing principle.

Brenda Ueland, in her 1938 book If You Want to Write recommends keeping a “slovenly, headlong, impulsive, honest diary”. The way she puts it:

Write every day, or as often as you possibly can, as fast as and as carelessly as you possibly can, without reading it again, anything you happened to have thought, seen or felt the day before.

In her amazing The Creative Habit Twyla Tharp talks about The Box. A literal box. Each project of hers gets a box which is full of items that document the active research and work on that project. It’s filled with objects, notes, files, clippings, toys and just stuff. Some people store things in files. She prefers boxes.

And, last but not least, the idea I had misunderstood so badly years ago, seems so clear today when I reread Julia Cameron’s words in The Artist’s Way:

There is no wrong way to do morning pages. These daily morning meanderings are not meant to be art. Or even writing. I stress that point to reassure the nonwriters working with this book. Writing is simply one of the tools. Pages are meant to be, simply, the act of moving the hand across the page and writing down whatever comes to mind. Nothing is too petty, too silly, too stupid, or too weird to be included.

It’s about re-contextualising your experiences, reading, thoughts, ideas, and goals in words. This serves both as a mnemonic and to increase understanding as the act of reframing it all in words, in black and white, serves to help your mind integrate it. It turns external ideas and information into integrated thoughts that you understand and can act on.

Flipping to the next page, I can also immediately see the one paragraph that later led to all of my notetaking misery:

Morning pages are nonnegotiable. Never skip or skimp on morning pages. Your mood doesn’t matter.

If you ever read her book, ignore this paragraph. Your mood does matter in the long run. Don’t beat yourself up about it. There are other ways to accomplish the same thing without torturing yourself. What’s especially galling is that I clearly didn’t finish reading the book at the time as its entire purpose is to prevent people from making the mistake that I made.

Once you take in these many approaches to writing and study them as wholes, as opposed to just teasing out individual components, you begin to spot a few common threads running through them, among both the Box and Map creators.

The first one is that the difference between the Box and the Map isn’t as great as you think.

Those who favour the Box maintain an evolving internal map of where they are going with the project. The purpose of the items in the box is to both make it easy for you to maintain that internal representation and to give it enough context to adapt it to changing circumstances.

Those who favour the Map instead flip this around. The map is external and evolving and serves to make it easy for you to maintain the context internally so that you can adapt the project to changing circumstances. The goal is the same. The methods are remarkably similar. It’s just a question of which bit is serving as a mnemonic for the other bits.

Evidence boards are a compromise between the two that shows just how little the difference between the two is in actual practice. Depending on how you look at it, the evidence board is either the items of the box pinned to a board or a map that has been loosely transposed over to a wall.

Which general approach you should choose is entirely personal. As the difference is primarily in mnemonic tactics, the optimal approach depends on how your own memory and other cognitive processes work. Some people’s memory is "out of sight, out of mind.’ Or, you might find it easy to remember details but have a harder time maintaining a big picture context. Some have an internalised heuristic or rule of thumb for how a project should work, so they only need reminders and bookmarks that they check against their mental rubric. Some have a hard time visualising the final product that is the goal of their project and so need a tactic that keeps them motivated and more observant of the bigger picture. People vary and so must their methods.

The tactic to use depends on how your mind works. Experiment. Try different approaches out. But, once you’ve found your process, trust that the overall process is roughly the same:

Collect #

All the things you fancy. Note down ideas and thoughts. Take notes on what you read. Take pictures. Sketch when the whim strikes. Collect what interests you in life using whatever method is the most convenient for you. Anne Lamott uses index cards. Twyla Tharp uses whatever can be collected in her boxes. David Hewson uses a notetaking app (Ulysses, last I heard). Some use pens and notebooks. Whatever you use, remember that these notes are necessarily only an intermediate form. They don’t become understanding or thoughts until you integrate them. You need to be able to review them, and storing them safely is always useful, but, paradoxically, notes aren’t the be all or end all of the notetaking process.

Contextualise #

The purpose of the various journalling tactics as well as some of the mapping tactics (like the evidence board) is to get you into the habit of reframing and contextualising your thoughts, your reading, and your ideas. By reframing them in words (or sketches) you integrate them which makes them available to your thinking and decision-making processes. If you don’t integrate what you collect, are just building an ever more intimidating database of opaque words and alien ideas.

An external brain is a brain that can’t drive your thoughts and actions and will just make your work harder.

A daily written journal is a common way to accomplish this integration. But people have also used daily sketches, voice memos (on tape in the olden days), or video diaries. The goal isn’t to preserve or convince but to reframe and understand in your own terms what you’ve experienced, read, and thought. Blogs work great. Twitter might be stretching it because of the character limit. Use whatever works for you.

Rule of thumb: let the contextualisation method match the bones of the project. A writing project benefits from writing tools.

Map #

The final part is the map, the bird’s eye picture of where you are, what lies ahead, and where you want to end up. It’ll start off vague, whatever tactic you use. As you work it’ll become clearer, no matter whether you’re maintaining it in your mind, on paper, or in an Excel spreadsheet. The map might end up being an outline, a diagram, a building plan, a list of tasks in Trello, or a list of issues on GitHub. It will change over time, but don’t worry if it doesn’t. It’s important to keep in mind that the map isn’t the end product, just one more tool among many to help you build the end product.

What does this all have to do with a notetaking app? #

The first, most obvious conclusion is that there is no one best method. The above meta-framework for notetaking is broad enough to encompass both Zettelkasten and Twyla Tharp’s boxes filled with stuff. If I’m right about notetaking methods being especially sensitive to individual variation in neurocognition, then there will never be one method or one app to rule all of notetaking.

It becomes a question then of deciding on what my own particular take on this software genre might be. And, if you’ve been following my earlier posts, you probably have some idea of the direction I’m taking. At least in broad strokes.

But the meta-framework doesn’t answer one, very important, question. One that people have been tackling since the dawn of humanity.

What happens when you need to collaborate with other people?

Because nobody, not even your lone wolf novelist, truly works alone.

So…

Next: the final entry in the Colophon Cards research blog series, where I write about how collaboration and sharing fit into all of this.